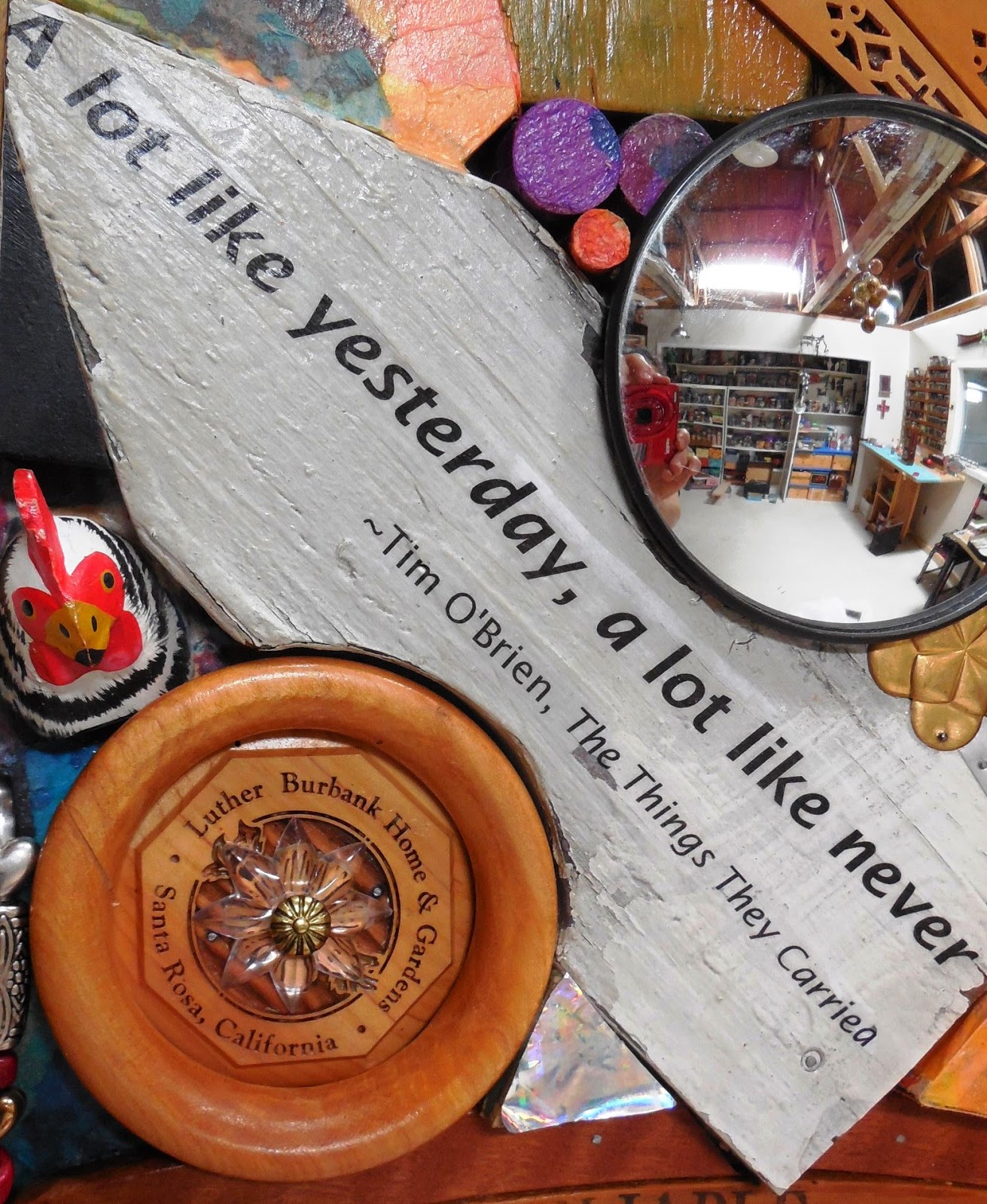

We didn’t ask ourselves who might challenge the book and why. When my 9th grade English class read The Things They Carried, our discussion did not include its history. A decade after its publication, and almost three decades after our war ended in Vietnam, O’Brien’s book was challenged for the very first time. At high schools in Pennsylvania (retained), Mississippi (banned), and Illinois (retained) in 2001, 2003, and 2007, respectively the years we declared war on Afghanistan and Iraq and the year General David Petraeus asked for and received an additional 20,000 troops to fight in Iraq. The Things They Carried has been challenged because of profanity three times.

Of the 4,000 troops that have died in Iraq and Afghanistan, we have only seen a handful of coffins and corpses, and our empathy has suffered for it. In 2009, the policy was reversed with one condition: the family of the deceased must give consent. The military argued that the ban protected “the privacy and dignity of the families,” while critics contested that it censored the human cost of war. A “true” war story must shock the conscience.īecause footage of dead American soldiers was such an important vehicle for Vietnam’s anti-war movement, in 1991, during the first Gulf War, the Pentagon banned media coverage of flag-draped coffins returning home. “You can tell a true war story by its absolute and uncompromising allegiance to obscenity and evil,” he writes. Violence occurs almost accidently, without warning, and for the sake of itself. Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried is a montage of graphic scenes: “Curt Lemon hanging in pieces from a tree” “The day Azar strapped the puppy to a Claymore antipersonnel mine and squeezed the firing device” “Kiowa sinking into the deep mulch of a shit field.” Like the photographs, O’Brien provides a more substantive reality that has no heroes or valor. In a war that measured its victory in Viet Cong bodies, photographs became a tangible unit for American loss-limbless GIs, an assembly line of coffins-these images made it home from Vietnam when our soldiers did not. Imagine the censor’s horror in the sixties and seventies: journalists running amok in the trenches, hitching rides into combat on the backs of convoys, snapping photos of Vietnam casualties.

When the boy hopped away, Azar clucked his tongue and said, “War’s a bitch.” He shook his head sadly. I remember how he hopped over to Azar and asked for a chocolate bar-“GI number one,” the kid said-and Azar laughed and handed over the chocolate. For instance, I remember a little boy with a plastic leg.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)